Hearing Nusrat is not just music, it is an act of worship. There seems to be a consensus amongst those who heard the maestro as he breathed life into notes. Defying the conventional genres that melodies are usually neatly stacked into, he would transcend to a level of rhythmic devotion that was lost on ordinary minds. Immersed in the spiritual, he never lost grip over any note or any tremor, his tehreek, mutki, phanday — nothing short of perfect. As the music washed over your senses and your pulse vibrated to the beat, you ached to fade into his mystical abyss, fully aware that what you were experiencing was not ordinary.

This was the magic of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

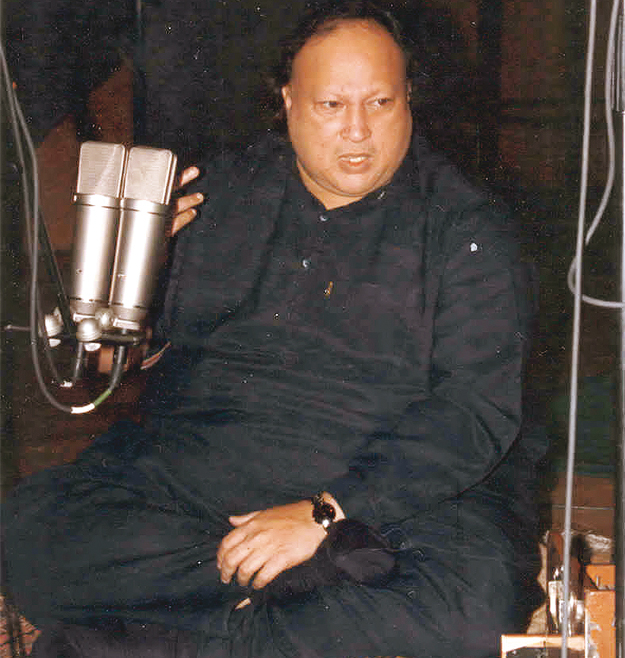

At Bidi Studio, Paris for a recording in 1993.

Pakistan did not have a Bocelli or Pavarotti at the time, neither did we have our own version of the Beatles or Led Zepplin, but it did not matter because we had Nusrat. Born in Faisalabad, he inherited a 600-year-old tradition of qawwali from his forefathers and went on to become the Shahanshah-e-Qawwali or the The King of Kings of Qawwali. But his genius was not just limited to qawwali. His collaborations with renowned musicians like Peter Gabriel and Eddie Vedder saw a marriage of the electric guitar and the tabla, producing some of the richest fusions of the time.

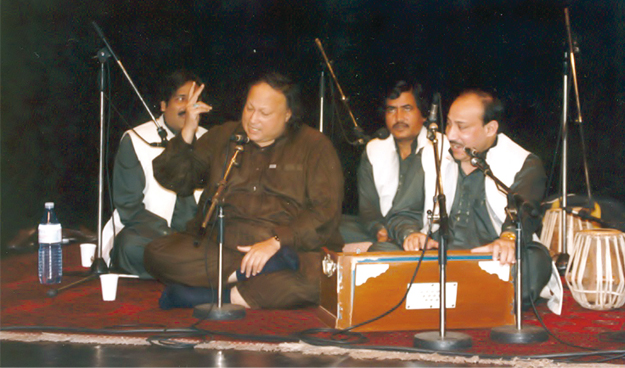

With group members rehearsing at Bidi Studio, Paris.

Unsurpassed in his musical range, his knack for improvisation and the sheer intensity of his chords made him one of the most significant voices from the region. While millions revered the musician, few knew Nusrat — the man. Dr Pierre-Alain Baud, a researcher, academic and author of his biography Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the messenger of Qawwali, spent several years in Nusrat’s company. In an interview during his recent visit to Lahore, he recounts his experiences with the melodic enigma.

1. What was your first exposure to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s qawwali music?

The first concert I attended took place in Paris in 1985 at Theatre de la Ville. It was organised by Soudabeh Kia, a French-Iranian lady. She was the first person to introduce Nusrat to non-resident Pakistani audiences, the same year as Peter Gabriel.

Featured in the 1997 issue of TIME magazine.

In 1985, Nusrat was still completely unknown in France, apart from some Sufi or South-Asian music aficionados. A major part of the audience that evening was Pakistani or Indian and the response was just like in Pakistan; people standing up from their seats and going down (Theatre de la Ville hall is very steep) to the stage to offer ‘vel’ (donations) or requesting him to sing such or such an item; a couple of sensitive listeners went into a trance.

2. And your response?

Oh, it was an astonishing discovery, widening my knowledge of Sufi music in a huge way. And Nusrat was such a presence. He had the Beloved floating in the air…

A-ma-zing, really a-ma-zing!

3. What can you tell us about your first meeting with Nusrat?

After this 1985 shock (as a mere lay listener among a 1,000 people), I heard him again live in 1988 or maybe was 1989. I had been listening again and again to his recordings. But the encounter moment came in autumn 1991. I met him when I was en route to attend his concert at an old French monastery. It was an autumn morning. We were at the Railway station in Tours, France. He was there, the ‘Singing Buddha’ from the Theatre de la Ville in Paris, waiting for the connection that would take him and his musicians to Fontevraud Abbey for his last concerts of the year in France. We, members of the enthralled audience who had already seen him perform thrice in Paris the week before, were going to the Abbey too, to witness the incredible freedom of his voice once again.

A group performance at Chergourg, France in 1993.

The shock this meeting produced was scorching. Uncertain, trembling words started a conversation, which slowly grew into a dense dialogue in the shade of the priory. Generous exchanges [were] interrupted by unexpected vocal demonstrations, stunning silences [and a] fiery look…Years later, having accompanied him on numerous international tours, I remained a spectator stunned by his vertiginous voice: I do not fully understand the mystery of his song, but an intimate resonance intrigues and unnerved me as soon as he sat down, cross-legged on the stage and hurled out his mad love song to the Divine.

4, This meeting at Fontevraud was the beginning of your association with Nusrat?

Yes. After the few days we spent together at Fontevraud, he invited me to follow him on his tour to Italy, and then to meet him at his home in Pakistan. From that point of time, I accompanied him for over five years, on a number of his international tours, in the capacity of an assistant of his major promoter. For the past 30 years, [Kia}on behalf of Paris municipal Theatre de la Ville, has been promoting numerous Pakistani artists worldwide.

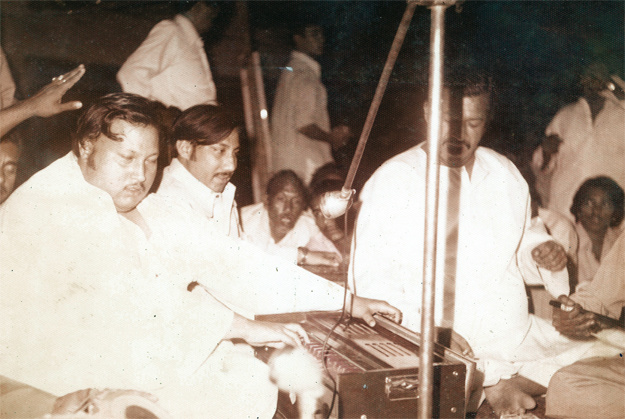

Performance at Lok Virsa, Islamabad.

I went with him to a number of European countries, Brazil, Tunisia, and was with him in New York. I followed him to dozens of places in Pakistan and went wherever he was going. He has been a great institution for me [with] respect to the Pakistani

society.

5. Say more about Nusrat the man.

He had innumerable facets: enigmatic and innocent, colossal and peaceful, inspired and ordinary, all parts of the same person who inflamed myriads of spectators in Lahore, Paris, Florence, Tokyo or New York, crossing linguistic and cultural, generational and social barriers with the greatest of ease. To further elaborate, I will quote myself from a fragment of the portrait I sketched about him in my biography foreword:

NFAK with his troupe.

“Singing Buddha in Tokyo, Quintessence of the human voice in Tunis, The Voice of Paradise in Los Angeles, The Spirit of Islam in London, Pavarotti of the East in Paris, Shahenshah-e-Qawwali in Lahore . Over the space of about 15 years, this chosen singer, one of God’s madmen, one of God’s sweetest, shot to planetary fame. And then he disappeared, too early…leaving a thousand footprints behind.

A man of superlatives: weight (impressive), octaves (six, supposedly), albums (125 at the beginning of the 1990s according to the Guinness book of records, maybe twice that many by now), videos that can be consulted on the Internet site YouTube (over 2,000, certain of which have been viewed a million times in a single year), concerts (by the thousands), Google references (hundreds of thousands), cassettes and CDs ( by the millions).

PHOTO: REUTERS

And yet a man of deep simplicity. His all-consuming mission was to spread a message — the kind and beautiful words of the Sufi poets, mystics, permeated by an Islam reflecting love and union.

A man outside of time, bewitching us with the madness of his declarations of love addressed to the Divine. A man truly of his times too, open to all kinds of experiments, all kinds of fusion. Rooted and universal. Committed and free.”

6. Who were the people around Nusrat?

Well, in Pakistan, basically his close family members, though I would say, at the same focal level, his qawwali party men, which included his younger brother, Farrukh, and for a long time his cousin-brother, Mujahid Mubarak, as well as his bother-in-law and other cousins.

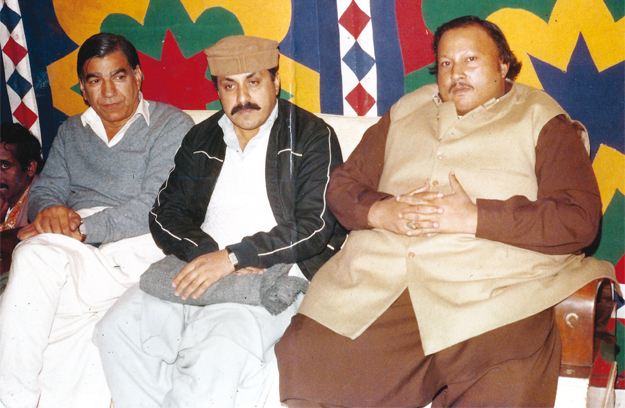

In his lodge before a performance, in Cherbourg, 1993.

In fact, he was spending much time with his party, always rolling from one concert venue to another, from a recording to a class, spending a huge amount of time travelling. He had hectic tour schedules.

7. I heard Nurat ate maybe 25 parathas for breakfast. Is that true? What was his favourite dish?

As far as I know, no! He was definitely a good eater (as we say in French). He appreciated eating but not [upto] this point. I am not sure [what his favourite dish was] but the most common one he was eating was roti and meat, the basic menu of Punjabi middle class men, no?

During different performances across Pakistan, 1993.

8. I heard Nusrat live in Central Park, New York, in the late 1990s. The impact of hearing his qawwali live is unforgettable. But when I hear Nusrat on CD it does not carry the same inspiration?

In the old days, the LP’s and records carried the full range of the singer’s voice — from the lowest to the highest pitch. Now CDs use stabilisers and other devices (for recording) and only capture the middle range of highs and lows. So you don’t get the full drama, power and passion of the vocalist.

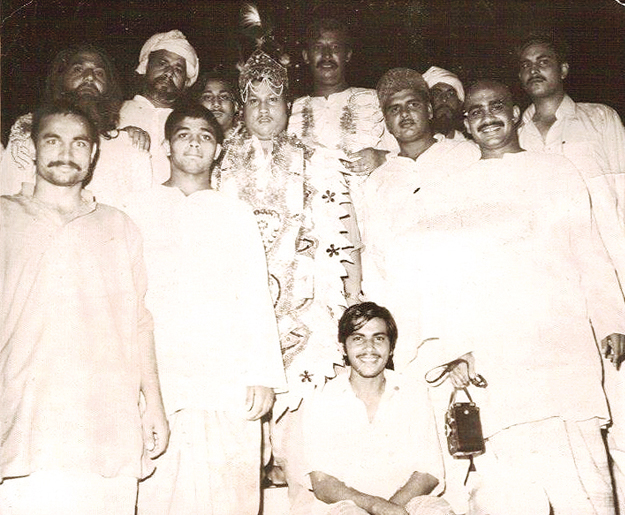

As a bridegroom.

9. Did your time spent with Nusrat change you in any way?

Definitely. He has been a major go-between, between my French European contemporary identity and my larger Sufi/spiritual/mystic individual soul, projected towards the Universal, the One.

At Rishi Kapoor’s wedding ceremony, Mumbai.

“Well, I think what stands out when you look at Nusrat is his devotion to Sufism. Qawwali as an art-form has a long history, and was used as a tool to bring people towards Islam. His family had a 400-year-old history, with the art.

I think for me what stands out is that he was the first real star to have come out of South Asia who was truly international. Madonna and Pavarroti wanted to record albums with him, Mick Jagger had come to Lahore to listen to him and there was a massive following across the globe.

He performed as a traditional qawwal for many years initially but could not attain the status of his father and uncle. It was really, Imran Khan who was then raising funds for his hospital, that changed things. Performing at those fundraisers, he met great musicians such as Peter Gabriel, Eddie Vedder and his reputation as an artist became global. This is his real impact, in such a short span he was the most popular Pakistani and the biggest celebrity to make an impact from South Asia.”

Socialite/Philanthropist – YOUSUF SALLI

“An underrated aspect about Nusrat saheb, is his ability as composer which most people tend to forget. On a broader level, modern music needed Nusrat, not the other way around. He was a complete package and had very different vocals, which appealed to a lot of people who collaborated with him.

He was a very good teacher and understood how to impart that knowledge to others. I come from a family of composers and instrumentalist myself, but Nusrat’s work as composer was very natural. Most composers have to think of a beat while composing the melody but for him this was inherent. I know RD Burman has used a lot of his work and AR Rahman is heavily influenced by him too.”

Musician – Sahir Ali Bagga

“I spent about 10 years attached to him and met him regularly even before that. His entire day was consumed by music — it was all he really needed. I recall many nights when we would end up singing or making compositions till dawn. I think what I loved about him was his work as composer.

When I had first started parody it was because of the increasing vulgarity in local theatre. I had always looked at parody as a way of paying tribute to our artists and stars. In Nusrat’s case, I remember the first time I performed in front of him, he was in a giggling fit. He ended up becoming one of my biggest supporters.

As someone who spent a lot of time with him, I can tell you he had very innocent and pure personality. I don’t think I have ever seen him lose his temper or get angry. But one thing was constant, he loved music and played 24 hours

a day.”Comedian – HASSAN ABBAS

“Unlike many musicians or individuals who consider music as something that is part-time, Nusrat was the complete artist, from top to bottom. His index finger would move in a rhythmic motion even when he was asleep. That was his genius, he was always lost in composition and music consumed his life.

He was a very straight-forward and kind individual who generously shared his craft and never paid heed to the commercial side of his career. In fact, I recall his manager at AlHamra asking him to take more of an interest because many people would make money from his music without giving his share. It was also known that he had composed a few songs for Bollywood and received something like Rs18 as payment.

But he was never bitter. Music was part of his blood and all that mattered.”

Academic/Writer – AQEEL RUBY

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, November 17th, 2013.